Web page reconstructed from the former website

http://www.manofthetrees.org

created by Paul Mantle

Richard St. Barbe Baker, (1889-1982), was the world's greatest forester. He was responsible for the planting of more trees than anyone else in history. He also was among the first ecologists to draw public attention to the global dimensions of deforestation and desert encroachment.

In Kenya, in 1922, with the help of 3,000 Kikuyu warriors, he launched the Men of the Trees, which became an international movement that advanced tree planting and conservation in 108 countries. He conceived and helped lead the efforts that saved the California coastal redwoods. He traveled the world as and advocate for trees and to share his plan for reclaiming the Sahara Desert through tree planting. He died at age 92 while on a global tour to promote environmental awareness.

The message of the Man of the Trees becomes more important with each passing day.

This is the story of his life.

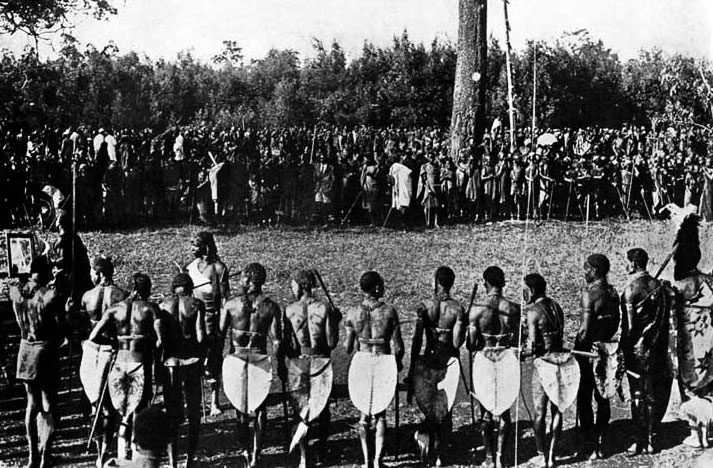

Into the clearing they streamed from between two hills: over three thousand warriors in full regalia, bearing spears and shields.

They formed into a circle before a giant tree. In accord with their beliefs, the tree had been spared to catch the spirits of all the other trees that had been destroyed in the area.

The place was the highlands of Kenya in eastern Africa. The warriors were members of the various clans of the Kikuyu people. The date was July 22, 1922. From the circle a young Englishman spoke through an interpreter. He told the armed warriors that to the Masai people, (their traditional enemies), they were known as the “Forest Destroyers.” The gathering stirred with anger. He went on to say that this was true: they had been forest destroyers. He called upon the warriors to now instead become "Men of the Trees" – sworn protectors and planters of trees. By doing this they would benefit their way of life, and improve the future of their people.

This was part of the first Dance of the Trees. What was the young man’s purpose in issuing this challenge to the warriors?

Why was he there?

At the entrance of his garden, the four-year-old boy had thrust two willow twigs into the ground to make an arch. Now, a month later, his arch had sprouted leaves.

His name was Richard St. Barbe Baker. He was born on October 9, 1889 in the south of Hampshire, England, in a country home on a sunny hill.

At the age of five, he went exploring in a deep forest of pines and ferns. He later described this experience:

"…I seemed to have entered the fairyland of my dreams… I had entered the temple of the woods. I sank to the ground in a state of ecstasy; everything was intensely vivid… The overpowering beauty of it all entered my very being …my heart brimmed over with a sense of unspeakable thankfulness which has followed me through the years..."

In the pastoral countryside of England where he grew up, woods and wild hedgerows have grown between the fields for hundreds of years. Here his father, who was also a minister, had a tree nursery. While Richard was still a young boy he helped grow thousands of seedlings and learned how to graft pear and apple trees.

"The Firs," the St. Barbe Baker family home,

West End, near Southampton, England

He became a beekeeper when he was twelve years old. By the time he was sixteen he had sixteen beehives. His best hive yielded 240 lbs. of honey in a single season.

In 1909, while still in his teens, Richard voyaged across the ocean to homestead in Canada. In Saskatchewan, he befriended the local Cree Indians, absorbed their lore, and learned nature survival skills. He also studied the ways of the beavers that built their dams near his tent camp.

True to a promise he had made to his parents to continue his schooling, he enrolled as one of the first hundred students in the new University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. To help support himself he wrote articles for the local newspaper.

He worked in a lumber camp near the town of Prince Albert and was disturbed to witness trees being harvested in an irresponsible and wasteful manner. It was then that he decided to one day become a forester.

He was also a “bronco-buster,” a tamer of wild horses. In Alberta, he was challenged to ride a black mustang from Montana that was considered too wild to tame and twice had escaped over a high fence. Richard rode him twenty-five miles the same day and had the horse given to him.

During his rides across the Canadian prairie he observed a troubling sight. Soil was being blown away from the farms. As much as an inch of soil a year was being lost.

He wanted to do something to help. He knew trees were the answer. Trees would break the blasts of the prairie winds, help hold the rainfall, shade and mulch the soil, and draw up water from deep in the ground.

He went to work at the university’s tree farm to determine which kinds of trees would be the best for the job. He imagined a future when the prairies of Canada would be protected by shelterbelts of millions of trees. This vision began to materialize during his lifetime.

Between 1916 and 1963 the Sutherland Forest Nursery Station of Saskatoon distributed 147 million trees. In one time span of less than thirty years, approximately sixteen hundred miles of field shelterbelts were planted on the Canadian prairies. Nonetheless, even today much tree planting remains to be done there.

After three and a half years in Canada, Richard returned to England and entered Cambridge University.

He was a twenty-four-year-old divinity student there when World War I erupted in the summer of 1914. Richard enlisted in the British army and served as a cavalry trainer in Ireland and then as an artillery officer and a sniper at the front lines in France.

During the war his thigh was broken in an accident with the horse he was riding. Later in the war he was wounded so badly from an artillery shelling that he was almost given up for dead. After recovering from these injuries, he was in charge of transporting horses – eighteen thousand of them in fifty-eight trips – across the English Channel to France. Twice his boats were sunk by underwater mines.

A third serious injury occurred later on land from an aerial bombing near the battlefront. As a result of this he was released from duty in the war with the rank of Captain.

Gradually he was nursed back to wholeness. He was then able to return to Cambridge University. However, he was faced with the question of how to pay for his education. The answer came in a dream.

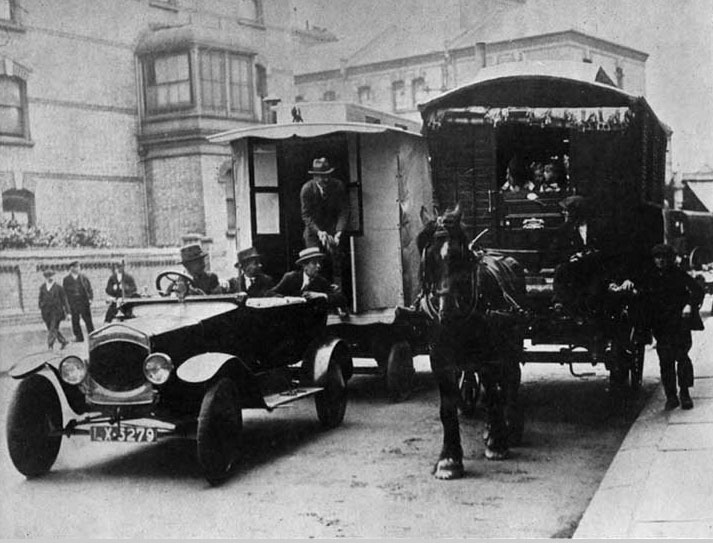

In his sleep, he saw the design for what became the first modern caravans, also called travel trailers. He used plywood and thirty-six airplane undercarriages, left over from the war, to build them. With the profit from his invention he was able to pay his way through Cambridge and earn a degree in forestry.

Caravan or travel trailer of his design

He was then hired as a forester by the British Colonial Office and traveled to an outpost in the country of Kenya in eastern Africa.

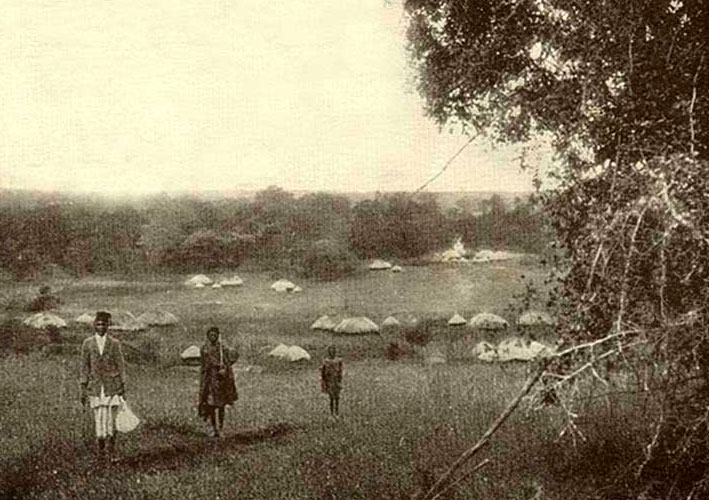

Highland Village in Kenya, circa 1922

In the highlands of Kenya, he saw that the soil was eroding away and the land turning into desert where the trees had been destroyed. He consulted with the chiefs and elders of the Kikuyu people and then shared an idea. The tribes always held a dance when they began something important – Richard called for a “Dance of the Trees.” Of the over three thousand Kikuyu warriors who took part, he helped select fifty warriors to protect the trees that would be grown to heal the land. This was the beginning of the Men of the Trees.

Five of the first fifty Watu wa Miti (Men of the Trees)

As the work unfolded, nine thousand tribesmen joined in planting and tending the trees. In a special ceremony, the leaders of the people made him a member of the Kiama, the council of elders. He is the only white man ever to be honored in this way.

Once, when a Colonial official tried to strike a Kikuyu farmer, Richard risked his career by stepping in between the two and taking the hard blow on his own shoulder. Richard’s African friends never forgot this act of courage.

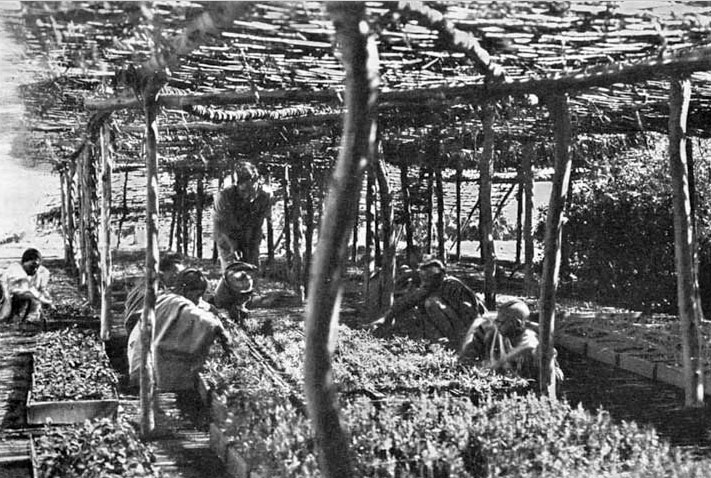

He left Kenya for three months to take part in tree planting in Tanganyika. He returned to discover that a Colonial official had destroyed eighty thousand seedling trees that the Kikuyu workers – volunteer Men of the Trees – had raised by hand. The trees had been eliminated to make a tennis court.

He was distressed by this wasteful act. However, with the help of Chief Josiah Njonjo, who had been his interpreter at the first Dance of the Trees, he conveyed to the Men of the Trees a plea for a new beginning. As a result, the warriors in the region grew over nine million new trees that year.

Part of the first tree nursery in the highlands of Kenya, 1922

Some of the Europeans living in Africa didn’t agree with Richard’s views and disliked him. They complained that he was "too involved with primitive people" and that he was a troublemaker for speaking out against certain tree cutting plans and practices. He never hesitated in his work – he had an abiding love and respect for the indigenous people of Africa and his belief in the importance of trees was also unshakeable. For the rest of his life he never quit striving to preserve old-growth forests and to increase the earth’s tree cover.

Richard knew that the loss of forest cover was a worldwide problem. He returned to England and began the Men of the Trees there too. He submitted newspaper articles and spoke on the radio and at a diversity of gatherings to inform the public of the crucial role trees held in the ecosystem. The Men of the Trees grew to advance tree conservation in one hundred and eight countries.

While in England in 1924, Richard encountered the Bahá’í Faith, a religion he went on to embrace and then serve for the rest of his life. Its main teaching is the oneness of humankind.

He returned to Africa, to the country of Nigeria, and worked and traveled several years there to help conserve the forests. He was the first European to learn the languages, customs, beliefs and stories of some of the different tribes whose territories he lived in and studied.

In 1929, Sir John Chancellor, High Commissioner of Palestine in the Middle East, requested that Richard come to that troubled region to establish a tree-planting program in the desert. (Palestine later became the country of Israel.) Some segments of the population there have a long history of religious and ethnic struggle and strife with each other. In spite of this, Richard was able to bring a cross-section of leaders from the religious and civic communities together under the name “Men of the Trees.” As a result, forty-two tree nurseries were rapidly established.

Next he went on a lecture tour of the United States of America. He arrived in New York with less than five dollars in his pocket. However, a publisher heard him talking about his experiences in Africa and asked if he would write a book. He paid Richard five hundred dollars in advance. While traveling, he wrote Men of the Trees – In the Mahogany Forests of Kenya and Nigeria, which included forty-eight of his photographs.

Richard St. Barbe Baker, 1932

Lowell Thomas, a famous radio personality, wrote the introduction to Richard’s book and became a friend. To help publicize the importance of trees, Lowell Thomas interviewed Richard on his radio show, World News, and gave Richard the name "Man of the Trees." He featured reports of Richard’s travels and campaigns in his broadcasts.

Over the years, Richard wrote thirty books, more than twenty of which were published. These, along with his lectures and the numerous articles he penned for newspapers and magazines, helped finance his worldwide forestry travels.

Richard went to California and gazed upon the magnificent redwood trees on the Pacific coast – some of the biggest trees in the world, many of them thousands of years old. He was shocked to learn that plans were in place to cut down most of the groves to make forms for concrete to construct the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

Redwoods cut in California

Upon his return to England, he focused on the protection of the California coastal redwoods. He launched the Save the Redwoods Fund in England, through the radio and newspapers, and by addressing groups of people of all ages wherever he could.

For eight consecutive years he returned to California, working with groups there to save the giant redwood trees. The American people responded by contributing millions of dollars. To their credit, the men in the lumber business cooperated with the effort and accepted less than market value for the trees. Finally, in 1939, a State Park of twelve thousand acres was created to protect the redwoods. Five thousand acres of National Park was added later.

Richard was a friend and advisor to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Governor of New York. Shortly after Roosevelt was elected President of the United States, he implemented and expanded Richard’s plan for planting millions of trees across the country. During the 1930’s, six million young men found employment in the Civilian Conservation Corps.

During World War II, Richard served in England as a Local Defense Volunteer, (later called Home Guard). He labored to prevent the deforestation of England and Ireland during this time and to insure that trees cut down for the war effort were replanted. After the war, he founded the Forestry Association of Great Britain.

The writer and playwright, George Bernard Shaw, was among the famous figures who enrolled as a member of Men of the Trees. Richard wrote wishing him: “The health of the pines, the strength of an oak, and the endurance of a redwood tree.” This is an apt description of the vigor that Richard himself applied to his forestry work.

In 1952, with the blessing of several major universities, he led an expedition that traveled nine thousand miles through the Sahara Desert. Despite the grave dangers of desert travel, he made the trip in a second-hand vehicle left over from World War II. He formed a second Sahara University Expedition in 1964, and covered twenty-five thousand miles around and in the Sahara. He gathered scientific data and compiled evidence that parts of the Sahara had once been covered with forests.

Nairobi, Kenya, 1953

Richard wrote two books about these expeditions, Sahara Challenge and Sahara Conquest. Some movie documentation also took place during the trips.

These gained publicity for his idea to stop the Sahara from spreading and drying up more land. He believed that the desert could be reclaimed by growing millions of trees around and in it, and that the military armies of the world could be put to work on this task.

Back and forth across the world Richard flew, from country to country, to advance the cause of forests. He resided in England and later New Zealand, but he visited many other countries, some of them repeatedly. He considered the whole world one homeland and himself a world citizen.

Everywhere he shared the message: “You can gauge a nation’s wealth, its real wealth, by its tree cover.” He said, “The health and the economic security of the human race depend on how well the forests of the world are managed.”

St. Barbe and The Ghost

His love for trees was often combined with his lifelong love for horses. In England, he went on a twenty-day horseback trip on a horse called “The Ghost,” and talked to children in seventy-two schools about the importance of trees.

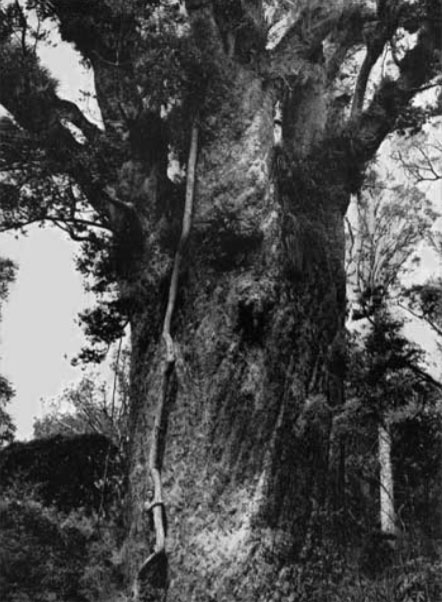

A Kauri Pine in its prime

Note the man at the base of the tree, lower left

When he was 74 years old he rode twelve hundred miles, on a dark bay horse named Rajah, from New Zealand’s northernmost kauri tree to its southernmost kauri tree. Throughout the trip he lectured on the Sahara Reclamation Program. On this horseback trip he also visited approximately ninety-two thousand New Zealand school children, and spoke to them about their tree heritage.

In 1963, when Richard was living in New Zealand, he learned that some of the California coastal redwoods were to be leveled for a new six-lane highway. Three days later he was in the United States. He met with Morris Udall, the Secretary of the Interior in Washington, D.C., and convinced him to present to Congress an alternate route for the highway.

Richard wrote: “The struggle to save the redwoods still goes on; it seems that each generation will have to fight to maintain their redwood heritage.”

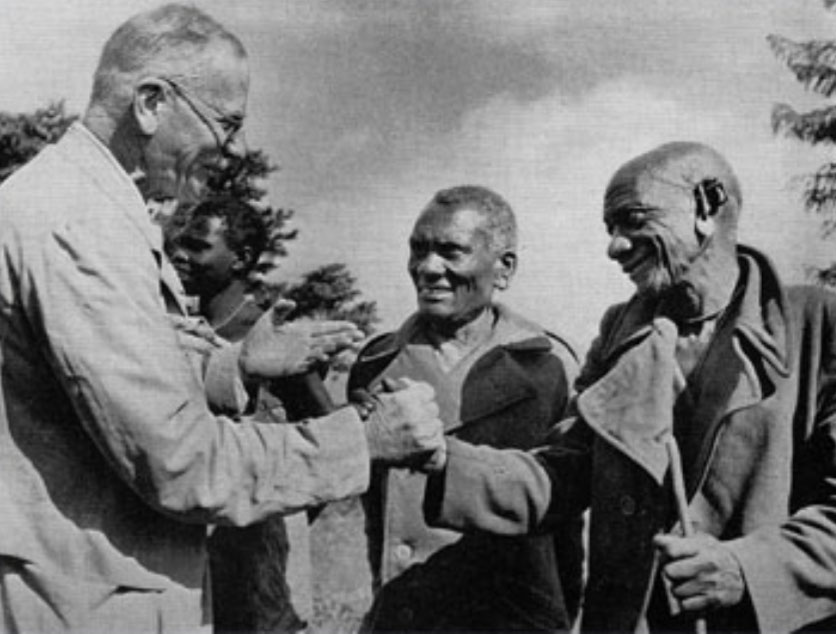

Old Friends Reunited

On a return trip to Kenya in 1966, he organized the planting of ten thousand trees in ten minutes with the help of ten thousand young people. Three days later, six thousand trees were planted in about six minutes.

Richard believed that saving, replacing and multiplying trees made it “…natural to think for the future, for other people, for generations yet unborn. Planting a tree is a symbol of a looking-forward kind of action; looking forward, yet not too distantly.” Thus he inspired others to perpetuate the earth’s green mantle. To cite but one example, after a visit from him in 1979, the Western Australian branch of the Men of the Trees was established and has since planted more than seven million trees.

Richard spoke to many world leaders during his long life. He conferred with kings, sheiks, prime ministers, chiefs, presidents, rajahs, dictators, and a pope. He proclaimed the importance of trees to all of them.

Prime Minister Nehru of India said to him, “Baker, I have read your book, Sahara Challenge, three times. Now what are we going to do about the Indian deserts?”

“The answer is the same,” Richard said. “Trees against the desert.”

Richard was awarded the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II in 1978 and the Prince of Wales became the Patron of the Men of the Trees in 1979.

Some of the most active members of the Men of the Trees have been women. In many places the name “Men of the Trees” has been changed to “International Tree Foundation.”

Originating in Kenya in 1922, the motto of the Men of the Trees is "Twahamwe," meaning "Pull Together," or "All As One." In that spirit, numerous organizations, groups, conferences, and observances have credited Richard St. Barbe Baker as being their founder, co-founder, guiding inspiration, or a leading public advocate.

In addition to the worldwide branches of the Men of the Trees and the International Tree Foundation, these include: the World Forestry Congresses, the Soil Association, Trees for Palestine, the World Forestry Charter Gatherings, the Save the Redwoods League, Tree Sunday, Children of the Green Earth, Friends of Nature, the Green Front, the Sahara Reclamation Company, Friends of the Sahara, the Forestry Association of Great Britain, the Year of the Tree, Arbor Day activities in countless localities, Trees for Life, the Tree Society, the EcoWorld Foundation, and the International Tree Crops Institute.

St. Barbe with friends in front of a forestry institute, Beijing, China

Richard never retired; instead he traveled and taught. While on a visit to Canada at the age of 92 – a few days after planting a tree – he closed his eyes and died peacefully. He is buried in a Saskatoon cemetery near two large spruce trees. His gravestone reads:

RICHARD ST. BARBE BAKER, O.B.E.

9 OCTOBER 1889 - 9 JUNE 1982

FOUNDER MEN OF THE TREES

PIONEER OF DESERT RECLAMATION THROUGH TREE PLANTING

CRUSADER FOR VIRGIN FORESTS WORLDWIDE

St.Barbe with children

He had been an originator of social forestry, an educator guiding populations all over the world to rediscover old tree planting customs and to create new ones.

He had proved himself a friend and champion of indigenous people around the world. He interceded on their behalf through the media, through governmental channels, through his writings, and, most of all, through personal interactions. He shared in their special relationship to nature.

Looking up

He was an ecologist long before the term was commonly known. For several decades he taught: “The forest is a society of living things, the greatest of which is the tree.”

He was the Man of the Trees, an earth healer, a visionary who saw a future of international cooperation:

"I have the dream of the whole earth made green again, an earth healed and made whole through the efforts of children: children of all nations planting trees to express their special understanding of the earth as their home, children of all races holding hands, circling the earth, expressing and celebrating their special understanding of all children as their brothers and sisters."

Richard St. Barbe Baker was responsible for the planting of more trees than any other person in history. When one considers the programs he initiated, the organizations he founded or co-founded, his prolific writings, radio and television interviews, lecture tours, press conferences, visits to schools and government agencies, and especially the meetings with heads of state, the scope of his legacy defies enumeration.

For instance, some remarks by St. Barbe (as he was referred to by his friends), at a luncheon with the President of Ireland, sparked a prompt doubling of that country’s tree planting program.

St. Barbe’s individual efforts and insights, bolstered by the World Forestry Charter Gatherings he began in 1945, effected changes in the science of silviculture at the planetary level.

His enthusiasm was boundless and contagious. Wendy Campbell-Purdy, an Englishwoman, heard St. Barbe speak about desert reclamation and bought a one-way ticket to North Africa, where she dedicated her life to establishing tree-planting programs in the Sahara desert of Morocco and Libya.

When St. Barbe was in his seventies he took flying lessons and briefly manned the controls of one of the world’s fastest jets on a trip to Moscow. He received a royal welcome in Russia where his book, Green Glory – The Forests of the World, was a forestry textbook being used by government departments. A summary of the book had been circulated in schools around the country.

Lauterbrunnen, Switzerland, Where the Trees Prevent Avalanches

His research into, and cogent analysis of, the world history of forestry – which he pursued for much of his life – provides a benchmark for future generations.

He traveled to Central and South America and was among the first to propose and plead for an economic solution from the international community that could halt the devastation of the Amazon rainforests.

At the age of 90, St. Barbe made the first of two trips to a remote area of the Himalayas in India where the women of the Chipko tree-hugging movement had, in desperation, taken a bold stand against the deforestation of the region. It appears that he was the first westerner to visit them in their villages and then publicly express support. He spoke out on their behalf with the full force of his prestige.

In the last year of his life, at the age of 92, he touched thousands of lives during a global tour to promote environmental awareness. A young Zhu Zhaohua, who became China’s greatest forestry scientist, met him that year in Beijing.

St. Barbe’s layers of accomplishment in forestry overshadow the energy he brought to other philanthropic and cultural endeavors. For example, in the aftermath of WWI he noted the large number of underclassmen at Cambridge suffering from war-inflicted disabilities. To aid them, he established on campus a therapeutic and productive Amateur Beekeeper’s Club, himself procuring the necessary patron, equipment and supplies and providing the training.

While on safari in Nigeria he encountered groups of outcast lepers in the jungle. He appealed to the Colonial medical establishment, which refused to acknowledge the lepers’ existence. At his own expense St. Barbe procured medicine, found a trained dispenser, and instituted a treatment center. Then he obtained seed from India and planted thousands of Hydnocarpus Wightaena trees to establish a future supply in Africa of (what was at that time) the designated medicine for combating leprosy. This entire incident did not even garner mention in his autobiography.

Youngsters Seeking Initiation in Kenya, 1920's

His writings and photographs depict ways of life and thought – some now lost – among the indigenous people of Africa that are a substantial contribution to anthropology. His forthright personal accounts of their telepathic abilities will fascinate generations to come.

Archeological dig at Tel Farah, 1929

While in Palestine in 1929, he spent three weeks filming, on four-hundred foot reels, Sir Flinders Petrie’s archeological digs of ancient Roman, Greek, and Hebrew ruins at Tel Farah, one of the far-flung cities of Judah. He filed news stories from the site with The Times of London. On the outskirts of Jerusalem, he oversaw the revival – which he had helped instigate – of the Feast of the Trees, with four thousand schoolchildren taking part in tree planting before sixteen thousand onlookers.

St. Barbe offered a creative response wherever he could. After WWI he successfully helped lobby for the creation of a Ministry of Health in England. At another time, through inspirational talks, he lifted fifty youngsters from lives of poverty in some of the poorest mining communities of England to new starts on farms in Canada. To assist Australian servicemen returning home after WWII, he made a film to convince the English public to eat Australian oranges. He headed a campaign to save the elm trees of Hyde Park in London. He wrote in support of land reform to benefit the poor in India, organized disaster relief after earthquakes struck Iran. He spurned ideological contention by praising the tree-planting initiatives of Russia and China, and Islamic countries Pakistan, Egypt and Kuwait.

The pace and range of his activities occasionally caught up with him. In conjunction with a serious illness in late 1974, St. Barbe’s surgeon gave him one more year to live. However, the medical prognosis did not take into account St. Barbe’s adamantine will, steeled by his sense of purpose.

He pulled through, only to resume his role as advocate and protector of the planet’s trees for eight more years and pursue a grueling globetrotting itinerary that boggles the mind.

Speaking of St. Barbe’s last years, when he was in his 80s and 90s, his friend, writer Paul Hanley of Saskatchewan, commented,

"…He never gave up, things like starting Children of the Green Earth and going to China primarily to work with children. It is interesting that when most people lapse into inactivity, he really got going. And he did it with nothing. He basically had no money when he was here...his friends sometimes bought him a plane ticket to get rid of him because it was so much work having him around, receiving visitors, planting trees, meeting dignitaries, media and so on."

Shaking hands in the Kikuyu fashion

Part of what made St. Barbe an effective catalyst and lobbyist for tree planting and conservation was an ability to convey the deepest concepts of ecology in a personal and compelling way to the public. He packaged education with stories; as his friend Hugh Locke put it, "St. Barbe was a raconteur" - a storyteller. And there were many stories to tell.

For example, in the course of his life and mission St. Barbe often faced death and serious injury. He was "smashed up" three times during WWI; charged by an enraged and wounded buffalo in Kenya; was shipped back to England to die in one of the multiple instances in which he contacted malaria; suffered blood poisoning and fought off a surgeon’s threatened amputation of his leg for three days after a shipboard injury; was crushed against a wall, during a stint as a mounted policeman, by a rogue horse that had already killed a man; exhibited severe lockjaw symptoms from a poison thorn; was completely blind for two days from tree sap that had splashed in his eyes (he credited a witch doctor for his recovery); retrieved Men of the Trees paperwork in the midst of an aerial bombing during the Battle of Britain; journeyed unarmed through bandit-infested badlands; spun desperate circles through quicksand in a secondhand vehicle in a remote tract of the Sahara Desert; traveled through military and guerilla war conflicts, such as during the Mau Mau “trouble” in eastern Africa ... etc..

All of the thirty books he wrote are now, unfortunately, out-of-print. Although some of them were hastily written – one was dictated in ten days while he was sick in bed – he was an able chronicler of one of the greatest adventurers of the era: himself.

Planting trees in corn and yams, early 1920s

Moreover, in even his earliest writings on forestry he advocated mixed age, mixed species plantings of native trees for symbiotic benefits, including the prevention of disease; the combination of forestry and agriculture to maximize land use; and sustained yield through selective harvesting techniques. He condemned the clear-cutting of forests. These insights, now finding acceptance, were outside the mainstream for much of his life. They have never been expressed with more conviction.

His notions of a sentient planet earth prefigured Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis. “Trees are like the skin of the earth,” St. Barbe declared. “If the being loses more than a third of its skin, it dies.”

If the story and message of Richard St. Barbe Baker had to be reduced to one word, that word would be "trees."

His contribution to the tree-planting component of the Civilian Conservation Corps was acknowledged by the bestowal of an honorary degree from the first forestry school in the United States at the University of North Carolina, Asheville. He also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Saskatchewan. These tributes took place during his lifetime; since then, in North America his achievements have been mostly overlooked.

Most significantly, his plans for an international undertaking to reclaim the Sahara and other deserts of the world through tree-planting have yet to be initiated on the scale he proposed.

Nonetheless he is, for all time, one of the twentieth century’s most colorful, versatile and important heroic figures. As the planetary environmental crisis deepens, the world will increasingly turn for inspiration and insight to the message of Richard St. Barbe Baker, the Man of the Trees.

PAUL MANTLE

Richard St.Barbe Baker

From the Funeral of Richard St. Barbe Baker

June 11, 1982, Saskatoon, Canada

"The word 'responsibility' comes to mind. We must investigate truth independently and respond to that truth once found and what a joy it is to see in an individual continuous response to act out these truths throughout an entire lifetime. This is the meritorious example we have in Richard St. Barbe Baker...

Six days ago we saw him struggle with superhuman effort to get from the car to a wheelchair to take part in a special tree planting ceremony on the banks of the Saskatchewan River. We saw him again, undertake a second difficult effort a few moments later to stand with the children around the tree to offer a prayer. While observing this effort we experienced the meaning of responsibility - responsibility before God, the results of which are a service to mankind..."

Prof. Otto Donald Rogers

"There is a vast sea of knowledge, still largely unknown, and much of it is forever beyond the wit of man, on the shores of which St. Barbe Baker was privileged to make his life. He ventured into the deeps with great skill and courage, and returned to share his new found treasures with his many happy companions.

Now he has flown from us on the wings of morning and goes to dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea.

Over the course of time, the original thoughts and life-long actions of St. Barbe Baker will have broader and broader impact on the peoples of the world. What greater memorial could the Man of the Trees ask for?"

Dr. J.W.T. Spinks

President Emeritus,

University of Saskatchewan

From the Eulogy:

"'He who plants a tree is a servant of God,

He provideth a kindness for many generations,

And faces that he hath not seen shall bless him.'

From The Friendly Trees, by Henry Van Dyke

Today we bless Richard St. Barbe Baker, a man who was responsible for the planting of billions of trees...

My life has been profoundly affected by St. Barbe and it has been my privilege to have known him for some ten years and to have been with him in his last days. I first met St. Barbe after winning the Men of the Trees prize, an award he set up here at the University of Saskatchewan upon receiving an honourary doctorate here in 1971.

I wrote a letter of thanks to him in England and eventually ended up visiting him while travelling there. He greeted me with such warmth and gusto, I was overwhelmed - it was as if I had been a lifelong friend.

It didn't take me long to see I was in the presence of a most remarkable man. At age 84, he was learning Chinese so he could ride horseback across Mongolia - one of the world's large deserts he had not surveyed for reforestation. Far-fetched I thought, until I learned that at age 76 he rode the entire 1200 mile length of New Zealand visiting schools and lecturing about trees.

This was St. Barbe. His whole life was full of vision and daring...

...No institutions could confine his imagination and zest for living. The organization he started, "The Men of the Trees," became a vehicle for formal lobbying and educational efforts; but as a self-appointed roaming ambassador for trees, the world was his home. He was truly a world citizen.

Wherever he went, he would begin mobilizing people and resources to conservation and tree planting efforts. Whoever found himself with him became his extra arms and legs - organizing lectures and talk shows and typing correspondence.

He gave himself totally to every situation he was in and he trusted that life would provide him with what he needed in return. This was part of his ecological law of return in action. While respectful of protocol and people, he had no qualms about visiting anyone, be they presidents or paupers, even without notice when there was a job to be done...

...He knew that true power came from surrendering our personal sense of power and pride in knowing, and plunging ourselves continually back into the unknown, the unseen source of life, love and creation... He gave every ounce of love that he drew from the depths of his being back into life.

With that giving, he died in our arms..."

Robert White

[Robert White went on to author Spiritual Foundations For An Ecologically Sustainable Society.]

Excerpted from the Introduction to Man of the Trees, Selected Writings of Richard St. Barbe Baker, edited by Karen Gridley, Copyright © Ecology Action, 1989

St. Barbe, His Ideas

Decades before the earth was photographed from space and understood as a unitary ecological reality, St. Barbe was practicing forestry from this global and holistic perspective. His view of the planet as a living organism anticipated the Gaia theory, which has provided such a fruitful base for scientific investigation in recent years. Very early in his career, St. Barbe began to see the complex ecological interactions within the forest as a mirror of the organization of all life. He believed that life as a property of the whole ecosphere is maintained by the synergistic interrelationship of air, water, soil and organisms. From this vantage point, he saw forests as a vital organ within the self-regulating, life-sustaining whole. Knowing himself as part of this whole, he felt the urgency of protecting, conserving and planting trees. He felt we human beings must “play fair to the earth,” to understand and serve this wholeness, which embraces all beings.

Gully Before

He also understood that ecological systems exhibit certain threshold responses. Thus removing too many trees over too large an area could dismantle a whole ecosystem and eventually disrupt the earth’s capacity to maintain critical life-support functions. His views against clear-cutting reflected this understanding. Similarly, planting trees could institute a regenerative cycle and bring degraded ecosystems to a threshold of recovery. These ecological concepts were only beginning to emerge in science at the time St. Barbe was describing and practicing them. The world is now struggling with the consequences of ignoring them.

The Same Gully 5 Years After Tree Planting

It is in this context that St. Barbe’s writings can be best appreciated. He possessed a scientific, aesthetic, and spiritual perception of the forest all at once. To the reader, he gives an appreciation of the wonder, beauty, and sacredness of nature, while at the same time teaching ecological principles and our responsibility to understand and respect them. To combine these dimensions he often relied on metaphors and parables, as in the case of his description of the forest as the living planet’s skin.

In the final analysis, St. Barbe lived his philosophy and it lived him. His life stands out as a model for a world desperately in need of the capacity to relate to the earth with respect, care, and responsibility. His life and his writings together demonstrate a vision of harmony between humanity and the earth. This is especially true of his efforts to tackle the Sahara Desert. The Sahara represented the largest man-made desert - an image of the destruction of the earth’s bountiful life. The Green Front program against the desert symbolized the potential to bring people and nations into cooperation with each other, and with the forces of growth and healing in nature itself. It demonstrated a faith in the capacity of humanity to transcend the separatist, non-synergistic tendencies of its nature. In this sense, his life invites human beings to become a force in guiding the evolution of life. His own integration of science and religion led him to see the potential for developing a mature planetary civilization based on ecological and spiritual principles. Fulfilling this potential remains the challenge of our age.

Perhaps the most visionary of the early environmentalists, Richard St. Barbe Baker travelled the globe from the late 1920s to the early 1980s, warning of the dangers of rainforest destruction, forest clear-cutting, and the greedy consumption of natural resources.

A widely respected forester, conservationist and author, his vision of the planet as a living organism anticipated the present-day Gaia theory, and his practice of involving people at the grassroots in protecting the environment foreshadowed current thinking in sustainable development.

In Kenya during the early 1920s, for example, Dr. Baker inspired thousands of Kikuyu tribesmen to help protect the local environment by planting trees. Their organization became known as the "Men of the Trees." His success was based, in part, on his understanding of how their own traditions and beliefs supported such a cause.

Among his legacies is the establishment of the World Forestry Charter Gathering, which was among the first international meetings to take a global view of the earth's ecosystem.

The first Gathering was held in 1945, and the meetings continued regularly through the 1950s and 1960s. As they grew in prestige and renown, the Gatherings stimulated several early instances of global cooperation, including an international proclamation of a Green Front Against the Deserts and support for the First Sahara University Expedition.

By the 1970s, it was felt that the Gatherings had been superseded by the establishment of other, more formalized international meetings and conferences on the environment, and the Gatherings were discontinued.

Nevertheless, as world events have shown, the world has not yet adequately risen to embrace Dr. Baker's call to protect and preserve our forests, which he called the "skin of the earth." In 1989, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Dr. Baker, the Bahá'í International Community revived the Gathering. And the 1994 Gathering likewise seems as relevant as ever.

Dr. Baker saw in trees and forestry a vital international resource. He believed that efforts to protect and re-plant them provided a tremendous means for social advancement and economic development.

Dr. Richard St. Barbe Baker, standing at right above, at a reunion in the 1950s in Kenya with original members of the Men of the Trees.

Dr. Baker founded the Men of the Trees in 1922.

It was one of the first environmental non-governmental organizations to be supported from the grassroots and to base its activities on spiritual principles.

"World afforestation is necessary because it is the most constructive and peaceable enterprise in which the nations could co-operate," Dr. Baker wrote in 1949, speaking of the need for the Gatherings. "It would check, stop, and reverse the advance of the deserts upon the good lands of the globe, and thus relieve the shortage of foods."

Dr. Baker's views about the important role that spiritual beliefs must play in giving an underlying motivation to conservation efforts were also ground-breaking. As a member of the Bahá'í Faith, he drew extensively on the Faith's teachings about the oneness of humanity and, accordingly, brought a distinctive global-mindedness and unifying spirit to virtually every project he undertook.

The theme of this year's Gathering was the Forest Principles, which were adopted, together with the forest management plan of Agenda 21, by the governments of the world at the historic 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Many of the ideas that Dr. Baker tirelessly promoted during his lifetime, through his writings, lectures and annual World Forestry Charter Gatherings, can be found in these Principles.

The Forest Principles recognize the need to protect the world's forests so as "to meet the social, economic, ecological, cultural and spiritual human needs of present and future generations..."

They also speak of the importance of grassroots participation "in the development, implementation and planning of national forest policies."

And they recognize that "all types of forests embody complex and unique ecological processes which are the basis for their present and potential capacity to provide resources to satisfy human needs as well as environmental values...."

Yet many were rightly disappointed when the world community was unable to produce a more far-reaching Convention on Forestry -- and speakers at this year's Gathering have sought to address that. HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, in particular, uttered a resounding call for the adoption of such a convention.

The aim of the 1994 World Forestry Charter Gathering was also to provide an underlying sense of moral and spiritual urgency as nations go about implementing the Forest Principles and the Forest Management Plan of Agenda 21 -- and move toward a Convention and beyond.

Some forty years ago, when Richard St. Barbe Baker began the World Forestry Charter Gatherings, he asked diplomats to St. James's Palace not only to report on the state of their nations' forests, but also to suggest how they might cooperate, as citizens of the world, to preserve, re-establish and manage this common heritage. At the time, this concept was novel.

Today, in our increasingly interdependent world, sustainable stewardship of the earth's forests is coming to be understood as inseparable from a range of other global issues - including the establishment of social and economic justice within and between the nations of the world, equality of the sexes, democratic global governance and the rule of law.

If integrated into international policies and action plans for sustainable development, this concept of global responsibility and world citizenship identified so long ago by Bahá'u'lláh, and later applied to the issue of forests by Dr. Baker, offers a distinctive new global ethic.

As environmentalists ponder how best to motivate the changes in attitudes and activities that will be necessary to create a sustainable human civilization, the work of Richard St. Barbe Baker - and especially his understanding of how religious belief can provide a vital motivation for environmental conservation - is certain to be increasingly recognized.

Reprinted from ONE COUNTRY, the newsletter of the Bahá'í International Community, Volume 6, Issue 2: July-September 1994. © 1996 the Bahá'í International Community ISSN 1018-9300

Published in Bahá'í World, Vol. XVIII: 1979-1983

In Memoriam

PASSING DISTINGUISHED DEDICATED SERVANT HUMANITY RICHARD ST BARBE BAKER LOSS TO ENTIRE WORLD AND TO BAHAI COMMUNITY AN OUTSTANDING SERVANT SPOKESMAN FAITH. HIS DEVOTION BELOVED GUARDIAN NEVER CEASING EFFORTS BEST INTERESTS MANKIND MERITORIOUS EXAMPLE. ASSURE FAMILY FRIENDS PRAYERS SACRED THRESHOLD BOUNTIFOLD REWARD PROGRESS SOUL ABHA KINGDOM.

Universal House of Justice

10 June 1982

Richard St. Barbe Baker

Ecology is not a new branch of science, but rather one newly appreciated by recent generations. This interest in the pattern of relations between organisms and their environment is no longer the preserve of academics; the general public's concern in this field has assumed an increasingly important profile. As with so many other areas of human endeavour, the questioning of inherited traditional values in the mid-1800s encompassed our relationship to the natural environment. One of the most important figures in articulating these questions and engaging the public in a search for new directions was an Englishman who became widely known as `the Man of the Trees'.

Richard St. Barbe Baker, usually addressed as St. Barbe, was born on 9 October 1889 at West End, near Southampton, in England. His long life as a forester, author and conservationist brought to many generations the message of the importance of the natural environment and, in particular, trees. His unique synthesis of the practical knowledge of a trained forester and an almost mystical vision of the role that forests play in the life of man served to inspire millions of people the world over to become involved in restoring what he referred to as `. . . earth's green mantle, the Trees'. He was the first Bahá`í to achieve international recognition for his forestry and environmental work, and so it is appropriate to examine not only the contribution he made to his profession, but also the influence of the Bahá`í Faith on his development.

As a young man, St. Barbe went to homestead in Canada in response to a call for Christian men to attend to the spiritual needs of settlers on the prairies. He bought land in the newly-created province of Saskatchewan, and devoted himself to building up congregations in rural areas. Then, in 1909, he enrolled in the first class of the University of Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon.

It was while living in the Canadian west that he first saw the effects of the sudden disruption of an entire ecosystem. The ploughing up of immense areas of prairie grasslands to create farms, with only sporadic compensation measures such as planting tree shelterbelts, resulted in much valuable topsoil being blown away. Similarly, when he began working at a lumber camp in northern Saskatchewan, he witnessed the unnecessary waste of trees as virgin forests were logged. He left for England in 1912, determined that one day he would be involved in forestry and conservation work. However, the Christian ministry was still his first calling, and he enrolled in Divinity at Ridley Hall, Cambridge. This pursuit was soon interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, in response to which he enlisted and served in France. Following the war St. Barbe returned to Cambridge and this time took a diploma in Forestry at Caius College.

Thus qualified, he went to Kenya in 1920 to serve under the Colonial Office as Assistant Conservator of Forests. In Africa he again saw evidence of the tendency to take too much from the land and to exploit excessively the forests. In the highlands of Kenya large tracts of land had been devastated by a combination of the introduction of goats, the clear-felling of forests and the arrival of white settlers. St. Barbe conceived a plan to restore the indigenous forests using a system under which food crops were planted between rows of young native trees. Several years of crops would be harvested before the trees grew to a size that necessitated moving to a new site, leaving behind a potential forest and demonstrating that supplying people's basic needs is not incompatible with managing forests. Thousands of tree seedlings were needed for the operation, and departmental funds that St. Barbe had at his disposal were negligible.

In 1922 he took a step, unprecedented at the time, to remedy this lack of funds. He consulted with the Africans themselves, approaching the Kikuyu Chiefs and Elders in the area and enquiring how their tribesmen could be enlisted to help with tree planting. He worked with them to develop a scheme for the voluntary planting of trees. This resulted in three thousand warriors coming to his camp from among whom, with the assistance of the Chiefs, he selected fifty to be the first Watu wa Miti, or Men of the Trees. They promised before N'gai, the High God, that they would protect the native forest, plant ten native trees each year, and take care of trees everywhere. The society of The Men of the Trees later spread to many other countries and its membership today includes men and women from all walks of life. His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales became the Patron of the organization in 1979.

In the last decade foresters have begun to realize that the answer to deforestation lies in persuading the local people that safeguarding their forests will protect their livelihoods, while planting new forests will actually enhance their standards of living. This approach of enlisting local people is now called `social' forestry. St. Barbe began implementing this idea half a century before it became accepted practice, and was the object of much criticism during his early days for becoming too involved with the indigenous people of Kenya and elsewhere. He lived long enough to see the climate of opinion change and to witness recognition of his pioneering work in helping to pave the way for the adoption of a new philosophy in forestry.

After leaving Kenya in 1924, St. Barbe went back to England where he read a paper on African Bantu beliefs at the First Congress of Living Religions within the Commonwealth. At the conclusion of his talk he was approached by Claudia Stewart Coles who introduced him to the Bahá`í Faith by explaining that his genuine interest in another's religion struck a sympathetic chord with the Bahá`í principles. Under her guidance St. Barbe studied the Faith and embraced it shortly after.

Silvicultural Experiment in Nigeria, 1920's

Although he was later appointed Assistant Conservator of Forests for the southern provinces in Nigeria and served in this post from 1924 to 1929, there was one event during St. Barbe's tenure in Kenya that prevented his ever rising higher within the ranks of the Colonial Office: a superior officer attempted to strike a Kikuyu worker with the butt end of a rifle and St. Barbe stepped in to intercept. He felt that it was an unfair action and took the blow on his own shoulder. Considered an outrageous act of insubordination at the time, the episode is still remembered by Africans. It helped St. Barbe in enlisting their support for his many tree-planting programmes. He was later to reflect that: `My discharge from the Colonial Service liberated me for much greater work in reafforestation and earth regeneration in other parts of the world.'

The first indication of the new direction of his career came in 1929 when the High Commissioner of Palestine, Sir John Chancellor, asked St. Barbe to apply the lessons garnered during his time in Kenya to help unify disparate religionists in the British protectorate. In a move that indicated his appreciation of the role of the Bahá`í Faith, St. Barbe's first action was to approach its Guardian, Shoghi Effendi, who became the first life member of the Men of the Trees in Palestine. Working closely with the High Commissioner, St. Barbe then went on to enlist the Chancellor of the Hebrew University, the Grand Mufti of the Supreme Muslim Council, the Latin Patriarch, the Bishop of Jerusalem and others, explaining that: `. . . there was no land needing trees more than Palestine and no land would respond so well to planting.' From this initiative, forty-two nurseries were established. However, St. Barbe realized that providing the seedlings was not enough, and so he set out to establish tree planting as part of the culture, as he had done so successfully in Kenya. To this end he was instrumental in making Tu Bi'Shvat (the traditional Feast of Trees) a national tree-planting day which is now taken up by most Israeli schoolchildren. In his project in Palestine St. Barbe had the active support of notables including Field Marshal Viscount Allenby and Sir Francis Younghusband. His ability to enlist the help of prominent figures was now combined with his appreciation of the practical side of forestry and an understanding of how to involve local people in his plans. Thus was set a pattern of action which was to result in the involvement of millions of men and women around the world in the planting of billions of trees.

For many, St. Barbe will be remembered for two of his undertakings which more than any others seemed to capture the public's imagination: his work to save large tracts of California coastal redwood trees, and his plans to reclaim millions of acres of the Sahara desert.

By the early 1930s the redwoods of California were under threat from lumber operations. Although there was talk of saving small groves of these trees, St. Barbe felt it was necessary to set aside an area large enough to sustain the natural climate needed for the micro-forest. He raised interest in his plans by lecturing extensively across the United States and Britain. With a modest financial contribution towards the `save the redwoods' project from The Men of the Trees in the United Kingdom, St. Barbe was able to attract the attention of the American public who in turn responded with contributions amounting to over ten million dollars. The result was that a natural reserve of twelve thousand acres of redwoods were handed over to the State of California to be preserved for all time.

In 1952, with the blessing of several major universities, St. Barbe led the first Sahara University Expedition. His book Sahara Challenge describes the 9,000-mile journey and outlines his conviction that the phenomenal pace with which the Sahara over the centuries was merging into the Libyan desert could be arrested, further encroachment prevented and reclamation undertaken if the correct action was taken. As in other areas, St. Barbe was ahead of the times in his vision of trees forming a `Green Front' against the Sahara and other deserts. Only recently have governments and international agencies such as the United Nations begun to properly address the issue of the spreading of deserts. And yet St. Barbe was aware of the root cause of this delay. He wrote: `The conquest of the desert will have to start with the conquest of the heart of man. We have witnessed tremendous strides in scientific research and inventions, but it is obvious that the spiritual advance of mankind has not kept pace with scientific progress.' He presented the challenge of reclaiming the Sahara as `. . . A One World Purpose' that `would unite East and West and be the scientific and physical answer to the world's dilemma.'

For many years following his acceptance of the Bahá`í Faith, people would often know St. Barbe for some time before learning that he was a Bahá`í, for he was also an Edwardian--a composite of convention, eccentricity and very strong principles--who found it difficult to discuss religion, let alone ascribe himself publicly to this `unconventional' Faith. However, as his friend of many years, David Hofman, said of St. Barbe's very first encounter with Bahá`í: `He always said that this was the beginning of his true life, and he realized that he derived so much benefit from these [Bahá`í] prayers that it was only fair that he should serve the Bahá`í Faith to the best of his ability.' Mr. Hofman also noted that: `. . . he spread knowledge of the Faith wherever he went and was greatly admired by Shoghi Effendi for his dedication to the cause of humanity.' He served the Faith throughout his life in his work as a forester and author. He wrote: `The simple act of planting a tree, which is in itself a practical deed, is also the symbol of a far-reaching ideal, which is creative in the realm of the spirit, and in turn reacts upon society, encouraging all to work for the future well-being of humanity rather than for immediate gain.'

A letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to St. Barbe on 31 May 1953 bears a postscript in the Guardian's own hand: `May the Almighty abundantly reward you for your splendid and manifold activities in the service of the Faith, and enable you to enrich continually the record of your greatly valued and meritorious accomplishments, Your true and grateful brother . . .'

St. Barbe died on 9 June 1982 in Saskatoon. Although he was in his ninety-second year, he was still full of plans and was working on his thirty-first book. Just days before his death he planted his last tree on the grounds of the University of Saskatchewan. He had gone full circle to return to the place which had helped kindle a vision that, fuelled by the Bahá`í Faith, aided the creation of a new understanding in the consciousness of men of the importance of trees.

HUGH C. LOCKE

Published in Bahá'í World, Vol. XVIII: 1979-1983

©1986 The Universal House of Justice

World Rights Reserved

In 1924, Richard St. Barbe Baker learned of the Bahá'í Faith and embraced it soon after. While he did not express this very openly, his life of service to humanity was in complete harmony with his Bahá'í ideals. When he went to Palestine to work on reforestation in 1929, he met Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith at its World Centre in Haifa. Shoghi Effendi became the first life member of Men of the Trees. When St. Barbe initiated his World Forestry Charter Gatherings in England after World War II, the Guardian sent a message of support to each of the twelve Gatherings. The following are three of these messages.

DESIRE TO EXPRESS TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING OR HIS MAJESTY’S REPRESENTATIVE AS WELL AS TO ASSEMBLED GUESTS MY HOPE WORK OF MEN OF TREES SO IMPORTANT FOR PROTECTION PHYSICAL WORLD AND HERITAGE FUTURE GENERATIONS MAY BE RICHLY BLESSED AND AT SAME TIME CONSTITUTE YET ANOTHER FORCE WORKING FOR PEACE AND BROTHERHOOD IN THIS SORELY TRIED DIVIDED WORLD. – Shoghi Effendi, Cable dated 23 May 1951 to New Earth Luncheon, London.

DESIRE EXPRESS ADMIRATION YOUR ESSENTIALLY HUMANITARIAN WORK NOBLE OBJECTIVE RECLAIM DESERTS SPIRIT CO-OPERATION FOSTERED BY YOUR UNDERTAKINGS WISH YOU EVERY SUCCESS. – Shoghi Effendi, Cable dated 21 May 1956 to World Forestry Charter Luncheon, London.

DELIGHTED STEADY PROGRESS ACHIEVED MEN OF THE TREES WORLD OVER ESPECIALLY HOPES PLAN RECLAMATION DESERT AREAS AFRICA. – On behalf of Shoghi Effendi, Cable dated 22 May 1957 to World Forestry Charter Luncheon, London.

[Section added to the original website materials]

New Earth Charter A Testament of Richard St. Barbe Baker

Man of the Trees - Selected Writings of Richard St. Barbe Baker Edited by Karen Gridley

Some Major Published Books of Richard St. Barbe Baker

St. Barbe was working on his 31st book at the time of his passing. The 17 books below were among those published during his lifetime. They are now all out-of-print.

The Brotherhood of the Trees (circa mid-1920's)

Men of the Trees - In the Mahogany Forests of Kenya and Nigeria (1931)

Among the Trees (1935)

Trees - A Book of the Seasons (1940)

The Redwoods (1943)

I Planted Trees (1944)

Africa Drums (1945)

Green Glory (1949)

Sahara Challenge (1954)

Kabongo (1955)

Dance of the Trees (1956)

Land of Tane - The Threat of Erosion (1956)

Kamiti - A Forester's Dream (1958)

Horse Sense - Horses in War and Peace (1962)

Sahara Conquest (1966)

My Life, My Trees (1970)

Famous Trees of Bible Lands (1974)

Articles

California Coast Redwoods (From World Order magazine, Fall 1967)

Sahara Reclamation: A Garden and a Paradise in the Making (From World Order magazine, Winter 1968-69)

Last updated 22 November 2023